The idea to found a Black Women’s Centre was born out of the incredible disappointment some twenty Black women experienced when they went to the Winter University Women’s Studies (WUV) in Nijmegen in December of 1983. They went to the WUV with great expectations, but had to endure, for the second time, a programme containing no subject whatsoever that had anything to do with Black women’s issues – the first time this same thing happened to them at the Summer University in 1981.

Flamboyant Nieuwsbrief 6 (June 1987)

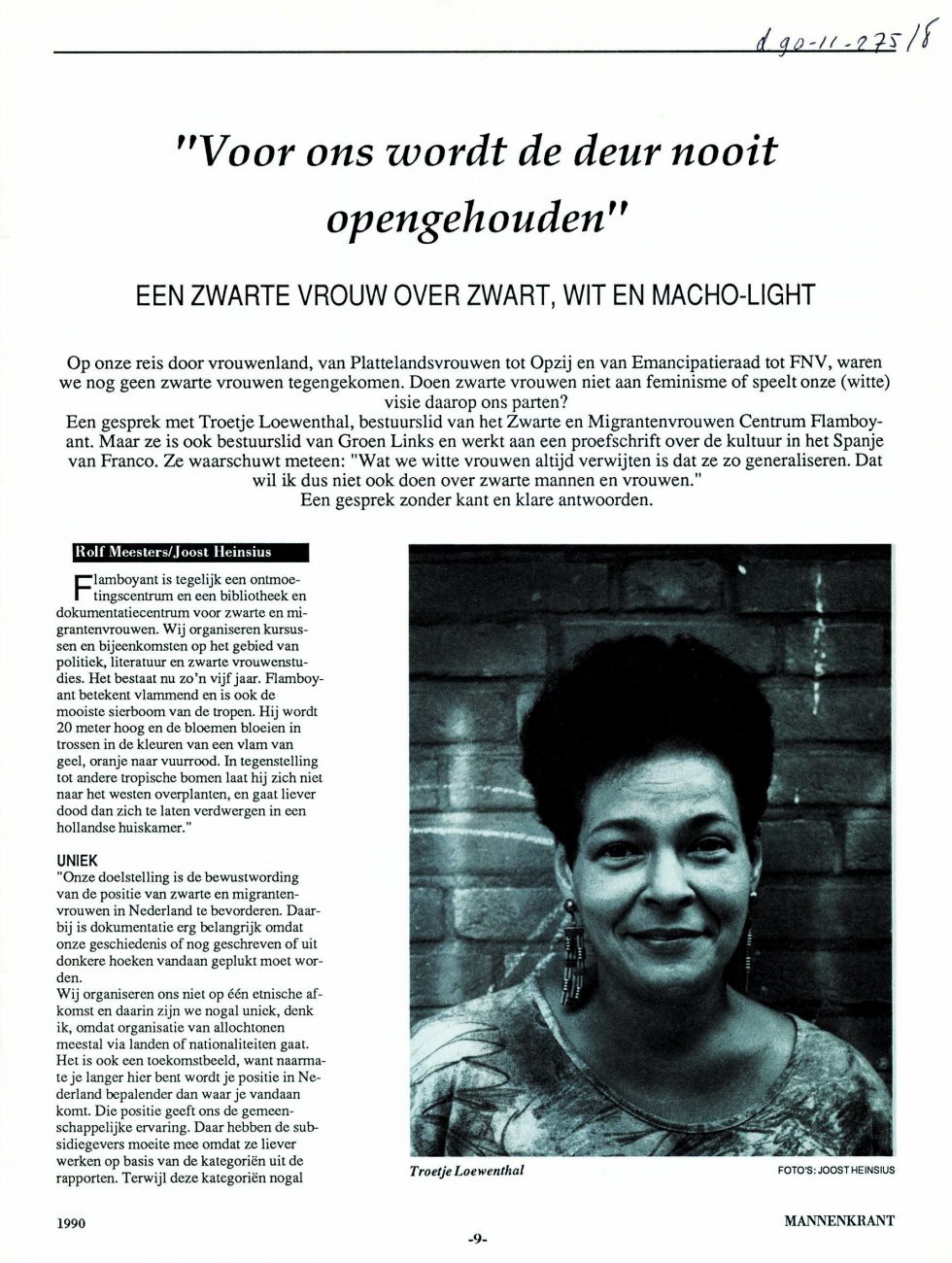

The group of Black women protested against this form of discrimination during the opening of the WUV and decided to create their own Black women’s group, which would have an independent agenda drawn up for each of the days. This also marked the beginning of a series of discussions regarding the need to found a Black Women’s Centre. This would be a central meeting point for Black women, where they could coordinate their activities, and a centre Black women could turn to in order to get information relevant to them, about anything.

An independent library and documentation centre is a deciding factor in this. Because for the many women’s libraries, archives and documentation centres in existence, none exist for Black women, that are aimed at their struggle, issues, and are set up with their vision. Such a library and documentation centre can focus on collecting information for and about Black women, and especially all information that was produced by Black women.”

In 1985, a group of Black women founded the Flamboyant foundation as a meeting place and documentation centre supporting the emancipation of Black, Migrant and Refugee (BMR) women in the Netherlands. Flamboyant carried out extensive research to take stock of what the situation was with regard to the information services for and about Black, Migrant and Refugee women in the Netherlands. By creating four bibliographies, they showed the importance of having an independent library and documentation centre. White documentation centres and libraries did not have the necessary perspective, vision, and orientation to find BMR information, and to make BMR information visible through relevant keywords.

Regardless of the need for an independent centre, government subsidies only existed for a project aimed at improving BMR information services within pre-existing libraries and documentation centres. Because the subsidies ceased, Flamboyant had to close its doors in 1991. The ZAMI foundation took over Flamboyant’s function of meeting place, and the International Information Centre and Archive for the Women’s Movement (IIAV) received subsidies to improve their BMR information services.

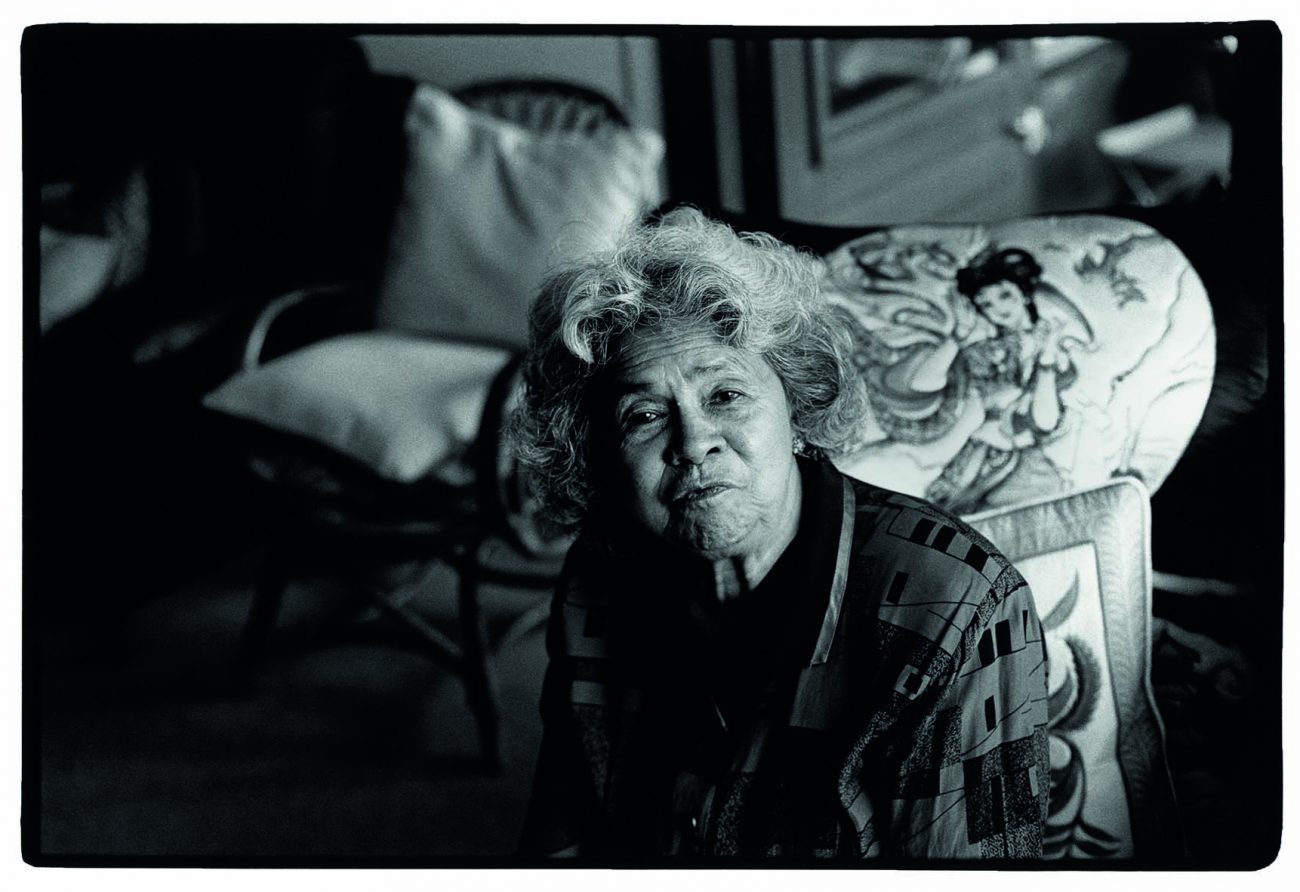

The three-year Project Information services concerning Black and Migrant women (zmv-I) launched in 1992, and was followed up with the Pattipilohy Project in 1997. This project was named for Cisca Pattipilohy who, through her experience as a librarian and documentalist, was one of the pioneers of BMR information services.

The BMR projects were intended to bring about a complete cultural change within the International Information Centre and Archive for the Women’s Movement, embedding the expertise in BMR information services into their day-to-day operations and general policy. To that end, aside from improving the Women’s Thesaurus and the information services, the projects also aimed to expand the collection of BMR materials. To that end, development of expertise was important. Cisca Pattipilohy says about this in 1998:

When an organization has insufficient expertise regarding Black women, it cannot build and maintain a good collection. In those situations it is possibly that only bestselling authors such as Arundhati Roy are acquired, and not important works such as The Empire Writes Back; a collection of articles from many Black scholars about the influence of white culture on Black literature. When the end result is a white collection with Black flavour, we will not have arrived at a good place.

Cisca Pattipilohy in: Naima Azough, ‘Multiculturalisatie kost tijd en geld: Het Pattipilohy project van het IIAV’, Lover 25:3 (1998)

To ensure the expertise was there, the importance of having a representative staff was emphasized, along with the sustainable maintenance of knowledge and contact with BMR women and organizations. To assess the kind of information that was needed, the Pattipilohy Project researchers conducted individual and group interviews with BMR women. These women stressed, for instance, the importance of the transference of stories that were not written down (oral history).

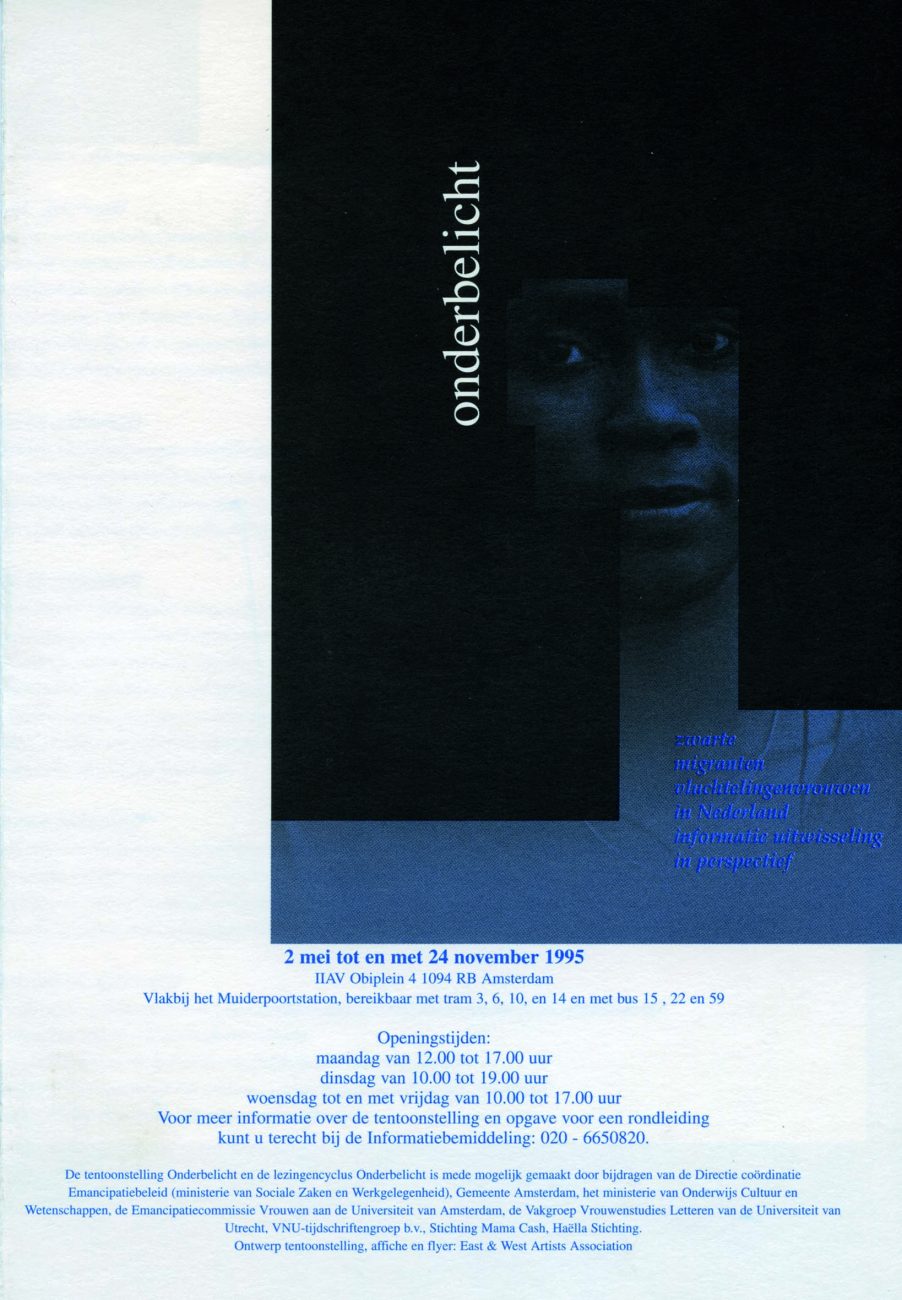

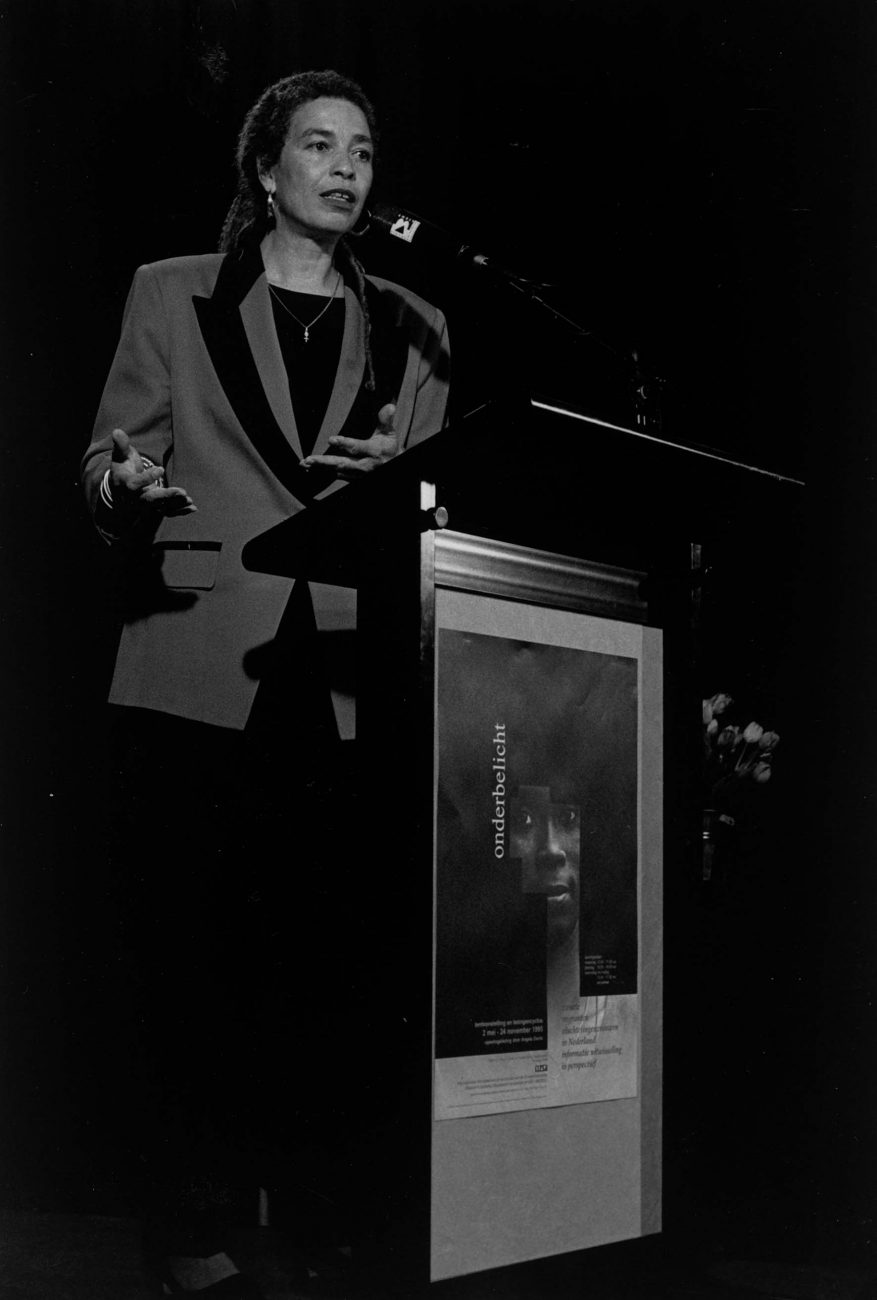

The BMR projects were also aimed at spreading BMR knowledge. An important result of the collaboration between the BMR information projects and BMR women’s organisations was the exhibition and series of lectures, titled Underexposed: black, migrant and refugee women in the Netherlands. In her opening speech on 1 May 1995, Angela Davis emphasized the international character of the struggle of Black, Migrant and Refugee women.

Angela Davis said in her opening speech:

“The Underexposed exhibition stands, as Gloria Wekker has emphasized, for the refusal of Black women to be erased from Dutch history. Underexposed shows that Black women exist, that they are part of the history of this country, that they are here and that they are here to stay!”

Angela Davis, ‘Iedere Amerikaan heeft een migrantenachtergrond. Openingstoespraak’, Onderbelicht, zwarte, migranten- en vluchtelingenvrouwen in Nederland, informatie-uitwisseling in perspectief (1996)