about the project

collection of gerrit Jan vos

Codes

I have sometimes asked myself: why did you pick out this particular photo? What effect did it have on you? Gerrit Jan probably applied some kind of criteria for selecting his photos, because otherwise he would have taken the whole box with a thousand photos from the flea market. He spent a lot of time in Berlin and, like me, lived there for a while. We used to talk about how you could buy loads of that kind of stuff at the time on the Ostbahnhofmarkt. It’s also possible that he had to buy a set of photos in packs, just like porno pictures in the past. There might have been two or three among them that he found attractive, but had to take the rest as well.

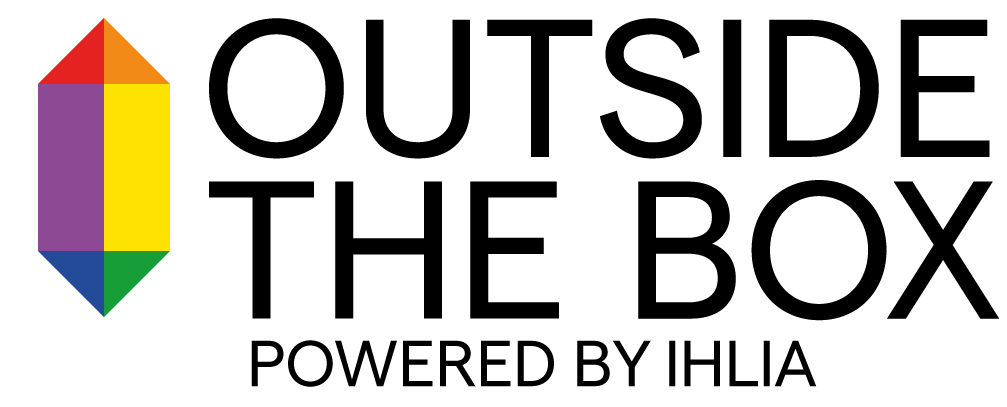

Compared with a few pictures that I find photographically really good, showing great technical skill with good composition and lighting, the above photo isn’t really very interesting. Perhaps Gerrit Jan was only concerned with the fact that it was an attractive young man who looked enticing with his half open shirt. What makes him extra attractive are those manly rolled up sleeves as he sits so respectably at his desk. It was for the same reason that Gerrit Jan occasionally also wore shirts with rolled up sleeves. At the same time, it makes the subject look like an active person: roll up your sleeves and get to work.

He may also have seen something in the photo which made him suspect that the young man was gay. I also recognise that tendency, sometimes unconsciously, to make an assessment about what kind of person someone is. But if I’m just walking in the street I can’t really tell whether or not someone is gay. It wasn’t like that 20 years ago, say: I could tell perfectly if someone was gay. I don’t know what it was, but you just knew. People give off subtle signals; they might be very small details: how they wear their clothes, their hair, their body language or a certain look in their eye. It’s hard to pin down what that look is, but you can often tell whether there’s something more than just friendship between men who go around together

There are a number of symbols to make clear what a person’s preferences are or to show that they belong to a certain group. The references to homosexuality have always been very subtle, and especially in the period represented in the photos collected by Gerrit Jan. Because we didn’t live in those times, it’s harder to recognise those signals. Yet there are still a few details which can give us a clue.

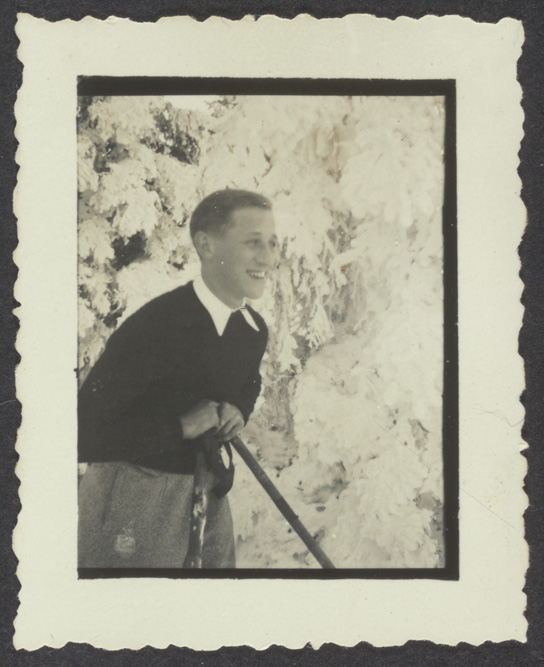

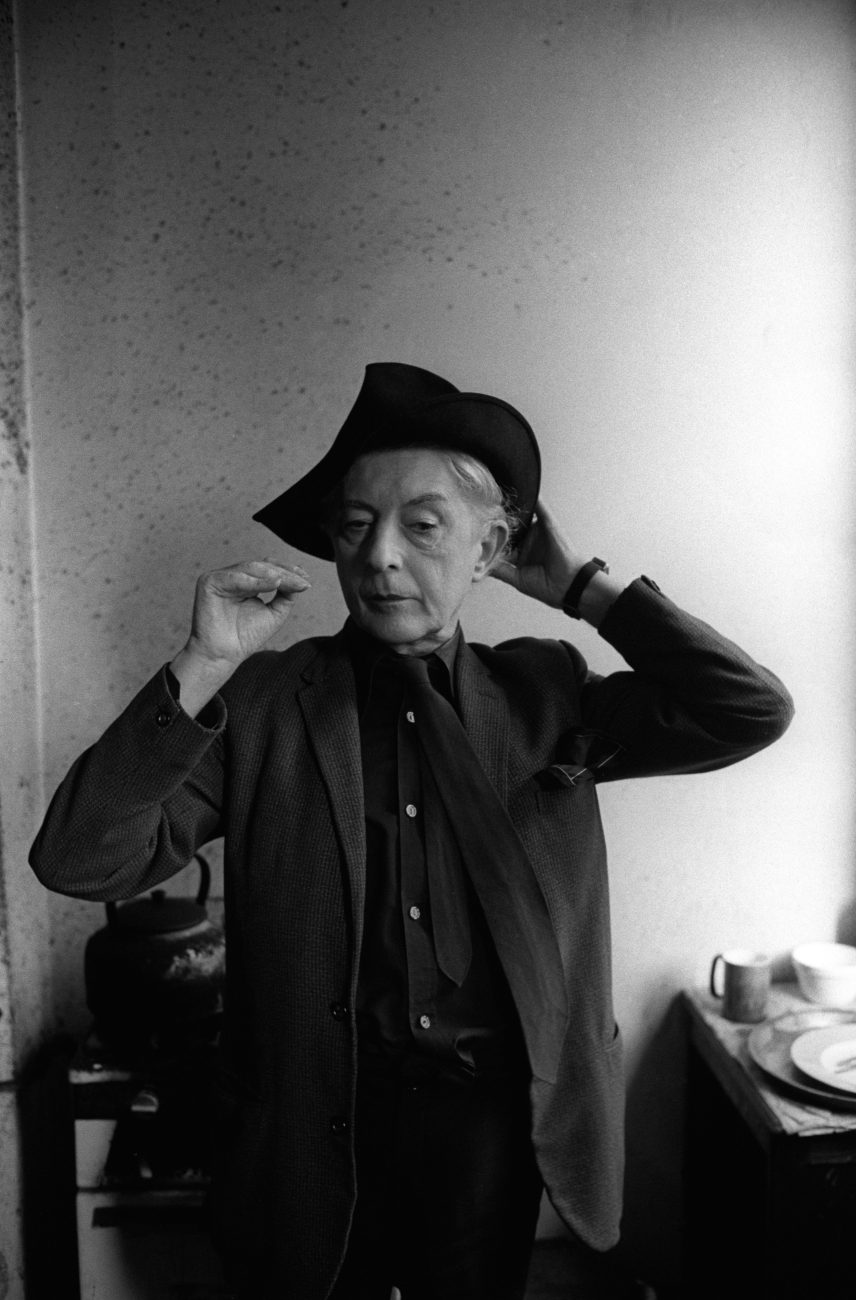

I can’t verify it personally, but when men started wearing shirts with a wider collar than normal, as in the left-hand photo – or wore a ‘Schiller collar’: a wide, spread collar, open at the front, named after the eponymous German poet – it was evidently regarded as very provocative at the time. Perhaps clearer is the very prissy photo on the right. The subject is holding a walking cane – not to help with walking but because he believes it is chic. You can be absolutely sure that this man is gay: with that silk scarf, left just a little loose, tied and folded just so, not simply crossed over. And with those gloves in his hand, something that the Queen also always does. A pipe was completely normal in those days, whereas moustaches and beards were out of fashion.

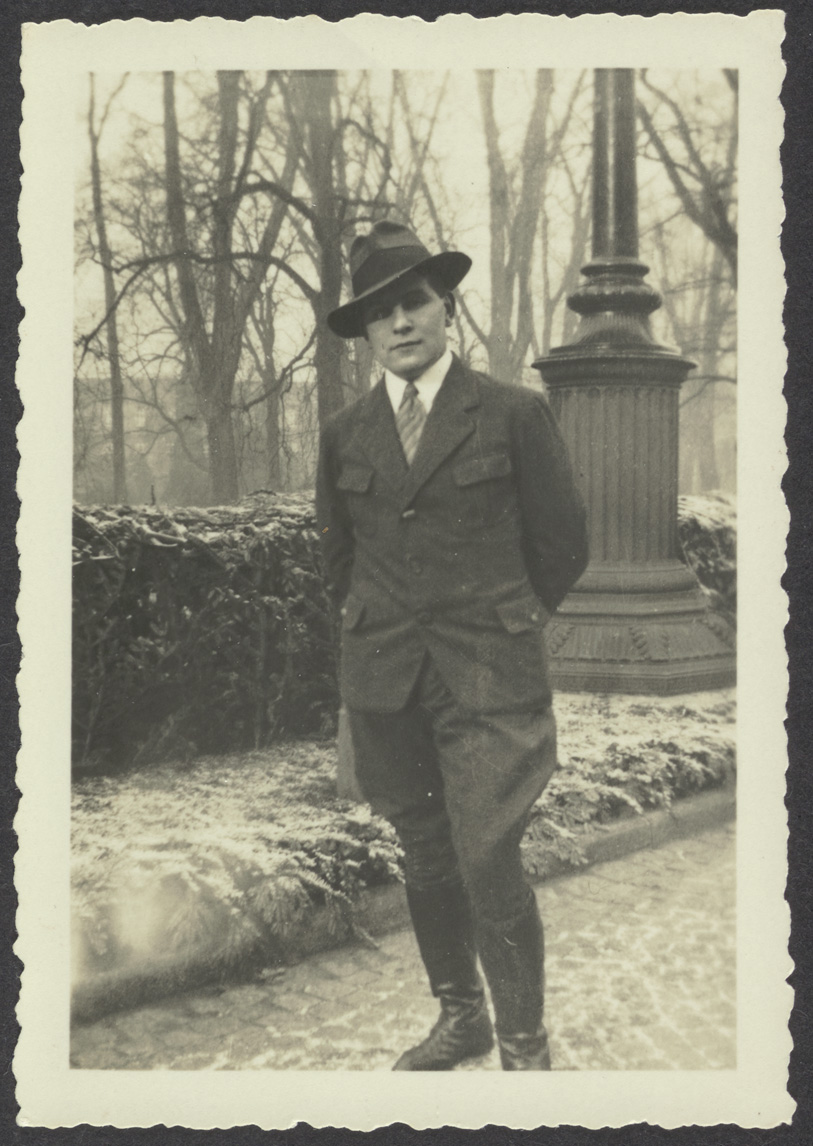

Another striking detail in this photo is the hat. The same goes for the men in the other photos. If I compare this with the photos of my father and grandfather in which they are wearing hats, they never wore them at such a steep angle. The position of a hat on the head can say a great deal; these men could very well be homosexual

A really good example of this is Quentin Crisp, a flamboyant figure from England who was also known for his humour. ‘Where homosexuals in the 1940s and 50s did their absolute best to be as invisible as possible, Crisp did the opposite, with his silk scarves, floppy hats and distinguished but always striking make-up.’1

The wave of emancipation that swept through the 1960s and 70s led to massive changes and the symbols and signals became clearer. There were the T-shirts with protest slogans, badges and small brooches, such as the broken rifle that was already being worn before the Second World War. It’s a slightly bleak irony that these were also worn whilst Hitler was in power. The best-known brooch is perhaps the pink triangle which emerged from the Nazi camps. But there was also the strange symbol that is almost never seen today, a kind of stylised Greek letter, which was worn on a chain to advertise the fact that the wearer was gay.

In the 1970s it was also the custom to wear a bunch of keys on your belt. And whether you wore it on the left or on the right said everything. A bunch of keys was more subtle than a handkerchief, because everyone had one. Whether you wore your earring in your left or right ear also sent out a signal.

Gay men adopt all kinds of characteristics from other groups, after which it becomes mainstream. At a certain point they began having tattoos, something that was previously reserved for criminals, seafarers and outcasts. They were worn on the biceps to accentuate them and make them appear larger. Fine, until the day my straight neighbour also had a tribal tattoo done. At a certain point gay men, often wearing a white T-shirt, all began sporting moustaches, until everyone started growing a moustache. I have four brothers; all of them had a pair of leather trousers, because that was the fashion. When my mother asked if I didn’t want to pair, too, I didn’t dare get any; I was far too afraid of becoming excited by them. I told my mother that I’d rather she bought me a pair of pleated trousers. It was funny, because my mother’s reaction was that wearing pleated trousers showed everyone that you were gay. A more recent example is young gay men starting to wear nail polish; now everyone does it. The nose ring of the true ‘gay pig’ is now also worn mainly by young teenage girls.

After a while, these codes disappear and gay men begin looking for new signals and codes to set themselves apart. If everyone is wearing one earring, gays begin wearing two. The next step is then a nipple piercing. A friend of mine who lives in Berlin told me that all the gay men there go to second-hand shops and rummage through the women’s department. They take whatever is on the rack that fits them – it makes no difference what it is combined with – and put it on.

So today I find it increasingly difficult to recognise all the codes and signals. I’m probably too old. It makes me wonder how today’s young people, in such an individualistic society, find those points of recognition, especially given that the way someone dresses no longer gives much of a clue, and lots of people wear the same clothes as my straight brother.

Lots of the photos in Gerrit Jan’s collection are group photos. Can we say something about them in terms of (hidden) codes? How ordinary, or just a step beyond ordinary, are these photos, like the two above? The soldiers are often just a bit too close to each other. They are holding each other’s hands, someone has an arm around his neighbour or a leg is laid over another. When I see a photo like that, in which someone has one leg over the other, it can be very ambiguous. It’s just like in historical paintings, where an open birdcage represented the presence of a prostitute. For me, that makes a photograph very erotic.

At the same time, you wonder whether these young men might have only held this pose for a brief moment before getting on with other things. Literally a snapshot of a single moment, just like taking a selfie with your friends today, when you grab hold of someone just at the moment that the snap is taken. It’s a sort of natural reaction.

Rank and status

Apart from the fact that it is difficult to identify the subtle codes and signals in the period when the photos in Gerrit Jan’s collection were taken, the world then was also a very different place. For example, if you were a bachelor, you weren’t allowed to rent a house on your own and had to move into rooms. It was also not easy if you wanted to forge a career. So what did you do? You kept your mouth shut or you set up your own trade.

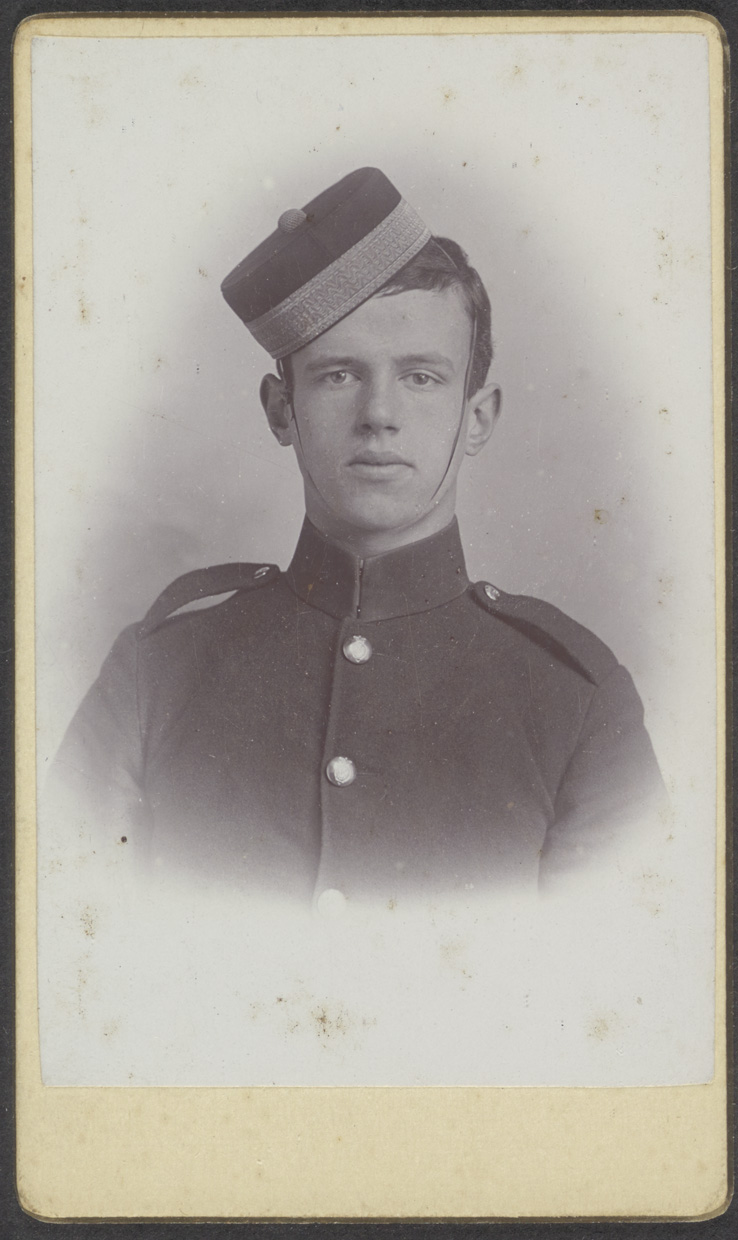

The army offered opportunities for career development. You started as a simple private and progressed to the rank of sergeant or corporal. Ideal when you’re young, working on the farm in a small village and feel you have few future prospects. It’s easy for the idea to grow that the army is where you belong. As an added bonus, you get to wear a fantastic ‘costume’ which also enhances your body.2 So you not only look good every day, you also have those career opportunities. In our house, too, there were celebrations when my brother was promoted from private to sergeant.

It’s also a reward system that is visible for other people. It confers status, especially for poor families. And if one child joins the navy and the other joins the army and comes home wearing a smart uniform adorned with stars and stripes, that provides a sort of upgrade for the family. It’s still something that very much occupies people today. The same thing is also evident from people’s school choices. There is a great shortage of tradespeople today, because it seems as if all the emphasis now is on academic achievement.

As well as a reward system, it can also be a punishment system. Where military uniforms exude authority, there are also uniforms which signify being subjugated to authority, such as school uniforms and prison uniforms. Prisoners can be depersonalised by making them all wear the same ridiculous uniform, so that if they escape everyone will recognise them. And in the Japanese police force, officers who had broken the rules had a stripe or armband stripped from their uniform and were forced to wear a Hello Kitty armband instead, as an embarrassing punishment.

The system of social advancement also applied in the navy and in the Catholic Church. Ultimately, anyone could become pope if they did their best. In Catholic families, one child traditionally had to be ‘sacrificed’ to God. He then entered the priesthood or, if he was a gifted learner or had a more adventurous nature, he could become a padre. If you were lesbian, you became a nun, and you could also become a teacher, which meant you could simply carry on working. That didn’t always turn out well, of course, for example if we think of the stories of child abuse; under a veneer of elegance and splendour, and whilst walking round in velvet and gold brocade, the most terrible things were perpetrated.

But ultimately the main thing was that you were among men – though that was not always necessarily sexualised. It did sometimes happen in the army that when boys and men were together – there were no women – and they felt the urge, they simply ‘did it’, even though really they had heterosexual feelings. At the time none of it mattered very much, but for homosexuals it offered a safe environment and the opportunity to be among other men.

- Bamber Delver Quentin Crisp (1999) in de Groene Amsterdammer. Accessed on: 19-09-2022 at https://www.groene.nl/artikel/quentin-crisp.

- See the article The erotic power of the uniform.