about the project

collection of gerrit Jan vos

Jan Willem Tellegen (b. 1956) studied Psychology and History at the University of Amsterdam (UvA) (1984). During his studies, his main interests were in the history of culture and ideas, and he was involved in the beginnings of gay studies at UvA. After graduating, he worked as a consultant in the private sector. Over the last ten years he has been heavily involved in volunteering and also writes boys’ fiction.

Male friendships and homosexual relationships

among German soldiers in the Third Reich

In July 1934, a series of murders was carried out in Germany which came to be known as the ‘Night of the Long Knives’. It was a political purge by Hitler and the SS to rid themselves of rivals of the Nazi regime. The purge also saw the murder of Ernst Röhm, leader of the Nazis’ paramilitary organisation, the Sturmabteilung (SA), who was also fairly widely known to be homosexual.

A speculative portrayal of his murder was presented in The Damned, the Luchino Visconti film from 1969, which portrayed the murders as having taken place after a drinking party with attractive young men, some dressed in drag.

It was common in Weimar Germany to make jokes about the Nazis being a bunch of homosexuals.1 Before 1934, several senior Nazis were known to be homosexual, and the sniggering about the intimate relations between Nazi comrades appears to indicate that at the very least, homosexuality was tacitly tolerated. Homosexuality and the masculinity cult of comradeship and deeply felt faith in the Volksgemeinschaft appear to be closely linked.

Whether or not that was actually the case, after the events of 1934 it was all brought to a brutal end. What is certain is that the SS and Himmler, who is regarded as having an almost paranoid homophobia, upheld a strict moral legal code, which made homosexuality in the SS and, by extension, in the Wehrmacht and other German organisations such as the Reichsarbeitsdienst, an untouchable taboo, a despicable assault on everything associated with masculine military honour.

Trial transcripts show that discovery attracted severe punishments.2 Detention or being banished to the front were the rule for soldiers found to be consorting with each other or with civilians.

Some got off more lightly, as the account of Hans Scholl illustrates; he rose to fame mainly because of his membership of Die Weiße Rose, one of the few resistance groups in Nazi Germany. Hans was arrested and tried in 1943. His family celebrated his heroism as a resistance fighter after the War, but omitted to mention that before the War, in 1937, as a member of the Hitler Youth, he and others had been punished for ‘indecent acts’. He was aged 17 when he had sex with the 15 year-old Rolf Futterknecht, and also engaged in incriminating correspondence with an older Swedish officer.

During his hearing he admitted that it had been a Schweinerei, but that he was motivated by ‘the great love that I had for Futterknecht’.3 A number of prison sentences were handed down, but Hans got away with a light punishment because he was young and foolish, rather than an incorrigible Volksschädling.

It seems simple. Friendship between true men was important, but sex between men was forbidden and led to imprisonment and subsequent posting back into the ranks. But even after 1934, a dual morality remained around the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ aspects of comradeship.

A great many words have been written, far more than can be dealt with here, about the culture of ‘multiple’ masculinity in the various uniformed organisations in the Third Reich.4 ‘Multiple’ in the sense that, for true men, true comrades, the bond, friendship and even love within a tightknit group of men was a central feature in different combinations of hard and soft emotions for each other. Masculinity combined strength and cold-bloodedness with a strong sense of love and servitude to the group. This was a core element of the Nazi ideology of the Volksgemeinschaft, in which individual sacrifice for the shared ideal and melding with the group took on religious proportions; deliberately hyped-up euphoria and eradication of individuality to create a feeling of a single will of the people in the enormous groups, as in the Nuremberg Rallies, for example, or with comrades in the army. Anyone wishing to get through it could not escape this. Uncompromisingly masculine in the drive for the victory, gentle and tender in the desire for friendship with comrades. The line between the two was a difficult and ambiguous one to tread.

The challenging question is: how to walk that line? What did the bond with army comrades mean? And how did the comradeship and love that soldiers felt for each other relate to individual desires, to the need for warmth and physicality? How did soldiers get along with each other, with their willingness to make sacrifices for each other on the battlefield through thick and thin, but also in the barracks, during the endless periods of boredom, without women, without sex.

Without sex? That cannot be true. All manner of things obviously took place between boys and men, both with each other and with civilians. Despite the trials and ego documents, we know little about it – much less than will have actually taken place. Also, in a free society people do not always shout about what they do, and there was every reason to agree a vow of silence here. In the new Nazi ideology after 1934, homosexuality was seen as a form of deeply worrying infringement of the masculinity ideal, precisely because uncompromising hardness and gentle friendship were so closely connected; but sex was put beyond a steel boundary. It was behind a forbidden door – so forbidden that it perhaps also proved a continual and toxic temptation.

There was a stark opposition between idealised emotions of friendship, which also incorporated physical rituals, and sexuality, which meant betrayal of those same emotions.

In the more senior echelons, in particular, gay sex produced strong feelings of dishonour and betrayal. A striking example in the Netherlands is that of Co Spreij.5 Spreij was a senior SS officer who was reported in December 1943 by two subordinates after allegedly attempting to engage in ‘homosexually tinted acts’ with them whilst in a drunken state. Spreij confessed straightaway, though precisely what he confessed to is not clear. It also made no difference whether he had merely knocked on that forbidden ‘door’ or whether it had been thrown wide open with abandon. What mattered was that the death sentence imposed by the Kriegsgericht military court was not carried out. Instead, in May 1944 Spreij was presented with a pistol on the orders of Himmler, with the expectation of taking his own life, which Spreij dutifully did. Such an exaggerated act carried out in order to preserve the honour of both the SS and of Spreij himself is suggestive of a kind of ‘cleansing ritual’ which had a symbolism that went far beyond simple execution.

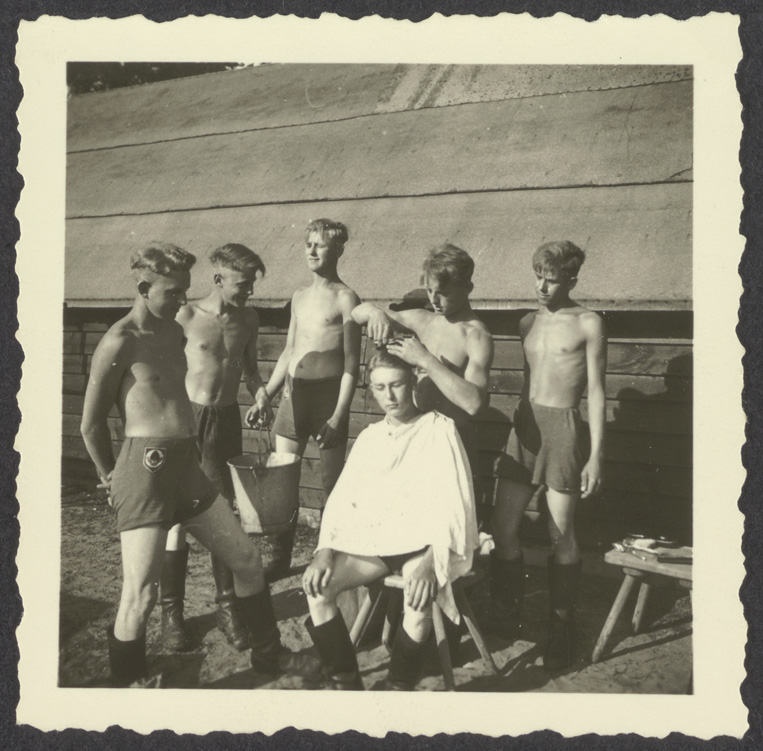

Bearing this kind of information from the literature and sources in mind whilst looking through the enormous photo collection of Gerrit Jan Vos offers a tremendous opportunity to see how soldiers interacted with each other in practice: silently, but in a variety of relationships with each other, in larger and smaller groups, in pairs and alone; in uniform but also in their free time, with naked upper bodies, cutting each other’s hair6 or in the unflattering shorts and swimming trunks which men wore at that time.7

What were they trying to express together? Who did they hope, know, expect would look at the photos? What were they trying to preserve for posterity? What was conscious, what was innocently thoughtless? There are not many photos which clearly show that it was a time of war; just a few photos of destroyed buildings with soldiers nearby. In that respect, the collection is one-sided. No SS Einsatzgruppen troops here standing by a pit filled with shot Jewish victims, or covered in dirt, frozen and dead in the mud of Stalingrad. We have to conjure up those photographs and those events in our own minds.

Most of the photos in the collection record a positive moment, either to mark an event or just taken informally because someone happened to have a camera. Some of them are snapshots; most are stiffly or informally posed. The subjects hold onto each other, draped on and around each other, happy to show the bond between them. The gatherings always look ‘positive’, laughing and happy. The collection mainly consists of photos the subjects could send home; proud faces: look how hard we are working, how much fun we are having and how smartly we march.

Comradeship requires a demonstrable show of bonding when photos are taken, with arms round each other’s waists and shoulders,8 occasionally arm in arm.9 Military morale and friendship bring soldiers physically close together, with shoulders and knees touching, sometimes holding each other playfully and teasingly, playfully mocking and being mocked, because this expresses comradeship, because it shows the bond between true friends, because it feels good.10 Squeezing someone’s arm ends with an embrace by way of conclusion. Perhaps it touches on the boundary of physicality which slips into eroticism; anything is permissible. Alcohol or tiredness increase the intimacy.11 And fantasising with the ‘gay gaze’ is okay.12

There are photographs in many armed forces of ‘role reversal rituals’, parties where young men dress up in women’s clothes and which appear to have everything to do with the absence of women and suppressed sexuality. As far as I could see, there were no such photographs in this collection. There are photos taken at parties with dressing up13, soldiers dancing in pairs14, but no transvestism.15 We do see some photos of dormitories with all the beds pushed together16, and sometimes soldiers in the same bed.17 But then, wouldn’t young men in the cold Russian winter have slept close to each other, simply to keep warm?

This collection does not contain many nude photos. Such photos do exist; naked swimming and sport certainly had a place in Germany’s Frei Korper Kultur. The nude photos18 that this collection does contain indicate that there was no prudishness about nudity.

Innocent pictures of men washing together, using the toilet19, tending the wounded, getting changed: the naked body neither hidden nor put on display. The rituals of male friendships in the army undoubtedly served to emphasise an environment in which bodies were simply normal and close by, a part of making friends for life, including dealing with each other’s emotions. Couples who touch each other always look a little more intimate.20 There are photos which, without knowing the context, appear so intimate that we see more than comradeship in them.21 But they are the exceptions; and it must be said that, in many of those informal, more intimate photos, it is often not clear whether they are actually of German soldiers.

The large number of photos also enables us to see where the limits lay. Putting your hand on your friend’s thigh was not done, for example. There are also no photos of men hand-in-hand with their cheeks against each other. Looking carefully, it is possible to see how far touching and intimacy went. Arms around each other, arms on shoulders, were an expression of friendship and bonding, even where the young men were half naked in the heat of summer.22 Often the soldiers are simply standing close together, without touching.

My impression is that when they are in uniform – a more formal moment – they less often have their arms over each other’s shoulders. In many cases the young men are close together simply because the group would otherwise not fit on the photo. To be honest, I do not see the exalted aspects of the official morality in these pictures. Comradeship is chaste, formal or giggly. There are a number of photos in which people playfully threaten each other through gritted teeth23 or which feature a pretend court martial24, but I see no sign of exaggerated ‘martial’ overtones, nor any emphasis on the hard aspects of masculinity. They are just young men playing leapfrog, pitching tents, digging trenches, raising flags or peeling potatoes. This last activity does have a degree of intimacy; the pan is in the middle, so the men are forced to sit in a tight circle,25 but the general impression is one of them just sitting there, enjoying the company of good friends and making the best of things.

The homo-social military culture thus also appears to be an easygoing hetero-culture, where the boundary with the homophobic space was easily kept at a great distance. Marking a forbidden boundary is almost unnecessary; remaining silent is enough, because it is not supposed to exist. Straight young men can love each other intensely, but sexuality is projected somewhere else, not on each other. This is no different from any number of other male communities. How a young man with desires for one or more other young men managed in the carefree ‘touching culture’ is also a well-known story. These young men found it especially difficult to keep up the innocent physicality of the comradely ritual, always uncertain at what point they might stray unwittingly and unnoticed across an invisible boundary.

In such a culture, an exalted taboo is not needed in order to keep homosexuality at bay, because it is so obviously out of place in the manly, shoulder-to-shoulder macho majority culture. It makes gay men easy and sad victims. They do things in secret, hold their tongues, suffer in silence, until fate – perhaps – intervenes. And it is questionable whether all the fine details of the official ideology actually reached the barracks and the boys from the villages and small towns. Klaus Theweleit’s two-part analysis of male fantasies (Männerphantasien) devotes extensive attention to masculinity and homosexuality in the Third Reich. He quotes from a letter from a soldier who recounts how fantastic it was to have sex with other soldiers in the army: “Für uns war alles so natürlich, keiner dachte an Pathologie oder Kriminalität; es war für uns ganz selbstverständlich” [‘It was all so natural for us, nobody thought about pathology or criminality; it just felt right’].26 By way of explanation, Theweleit suggests that sex in the army was a more or less unconscious act of undermining the patriarchal discipline, a symbol of resistance and elevation above the power of the officers. He could be right.

It could also simply be a matter of plain old sexual desire. Crossing boundaries, to be sure, and a more serious offence in the army than in civilian society, but I personally am struck particularly by what that soldier – clearly being careful not to be discovered – writes: ‘It just felt right’. They were just normal, impulsive boys at a far remove from ideological or intellectual ideas about morality and identity. That’s how it must have been for Hans Scholl, and luckily for him, as a member of the Hitler Youth he got off lightly. Not so Co Spreij, who moved in very close proximity to the ideological powers that be. For him and those around him it was a matter of honour, a penalty paid with a pistol shot.

- Martin van Amerongen – Kameraden in het kwaad. In: Groene Amsterdammer nr 25, 1995. It contains juicy details and examples of jokes about the ‘faggot culture’ among the Nazis before 1934. For example: ‘A certain member of the SA/ was so attracted to Ernst Röhm one day / that in order to impress him – what a farce / he had ‘Heil Hitler’ tattooed round his arse’.

- Pieter Koenders – Tussen christelijk réveil en seksuele revolutie. Amsterdam 1996, e.g. pp. 406-415. This is about the Netherlands and about trials in military organisations following discovery. No one in the army was of course openly gay, and prosecution of homosexuals as such is therefore another, complex story.

- Judith Schuyf – Leve de vrijheid! Hans Scholl, de Weiße Rose en het leger. In Gaynews 333, May 2019 pp. 32-35 and 334 June 2019 pp. 32-37.

- Thomas Kühne – Protean Masculinity, hegemonic masculinity: soldiers in the Third Reich. Central European History, September 2018, Vol. 51, No. 3, Special Issue: Masculinity and the Third Reich, pp. 390-418.

- https://www.westervoort1940.nl/spreij.html

- [Codes Vos Photo collection] 7185, 6951.

- 7099, 8635, 9320.

- 8683. The collection contains a great many examples of such photos.

- 7757, 7087, 9186.

- 8687, 7143, 8518, 9079

- 8658, 7834, 6931. 8834 is a sort of uniform pinup taken by a photographer who is lying on the ground.

- See for example 7846, 6890, 6898, 6951.

- 6952, 6958.

- 8488.

- 8619. Two soldiers with bosoms? Or is it simply the way they are posing because of the shape of a piece of equipment?

- 9295.

- 8939.

- 9278, 8656, 8566, 9278.

- 8615.

- 9079, 6935, 7085.

- 6904, 7134, 7152, 8050, 8480, 8539, 9067, 9079.

- 7002.

- 8673, 8978.

- 8696.

- 9949.

- Klaus Theweleit – Männerphantasien II, Frankfurt Main 1978, p 368.