about the project

collection of gerrit Jan vos

Gerrit Jan Vos and Els de Baan (b. 1959) were direct colleagues at the Fashion Department of the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. As a fashion historian she regularly writes articles on fashion for the Dutch newspaper Trouw and she is (co-)author of various publications on fashion-related topics. She is also an appraiser of textile objects for museums and individuals.

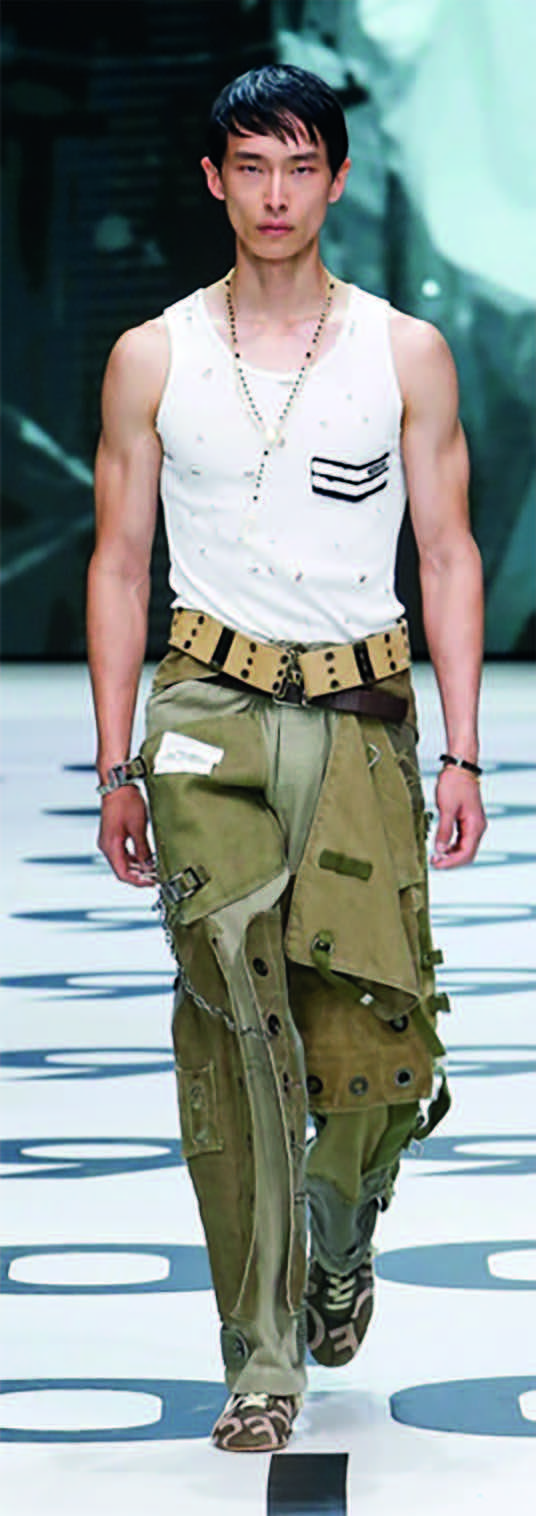

The relationship between military uniforms and model clothing has a long tradition. The ubiquitous trench coat even refers directly to the trenches from the First World War. The T-shirt worn by sailors, the flying jacket, the RayBan aviator sunglasses, the khaki chinos worn by the US armed forces, the duffel coat (or ‘Montgomery’, said to refer back to Field Marshal Montgomery), the balaclava and the knapsack: these have all become common items in everyone’s wardrobe. The same applies for accessories deriving from military tunics such as epaulettes, lanyards, insignia and of course the constantly recurring camouflage prints.

As well as these items related almost directly to military apparel, military clothing is also an inexhaustible source of inspiration for fashion designers. In virtually every fashion season, men’s and women’s outfits are paraded on the catwalk in which designers have made playful use of elements from military uniform.

But a military item can also go on to lead an entirely independent life, as with Dr Martens footwear, for example. Their high model is inspired by the traditional military boot. The company is introducing a collection of sturdy shoes and boots for the autumn/winter 2022 collection, under the rather rebellious-sounding campaign slogan ‘Made for wearers who want to shake up society’.

It is no coincidence that this type of footwear was worn from the 1970s onwards by punks, squatters and skinheads as an anti-establishment symbol. Although today’s wearers represent a broad spectrum of ideas, the manufacturer still markets this footwear as a ‘counter-culture’ brand.

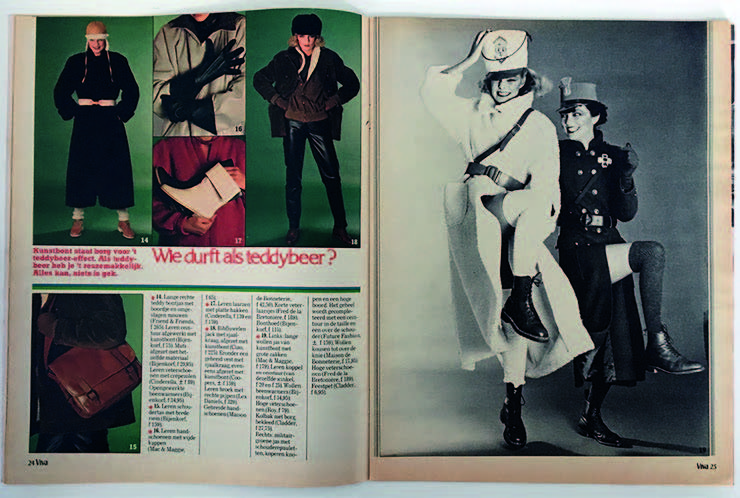

At the end of the 1970s, ready-made fashion clothing often included items derived from the military wardrobe. The influential weekly women’s magazine Viva (‘because it’s good to be yourself’) regularly published fashion reports with cover texts and titles such as Become a soldier, Playing soldiers, Sailor style and Fashion with daring: who dares?1

The clothing depicted in the Playing soldiers piece came from the army surplus stores, which were very popular at the time. A pattern was included so that readers could make their own embellishments such as belts, kepis and upstanding collars. Medals and decorations bought from party shops completed the image.

The ‘daring’ fashion referred among other things to a black-and-white photo of two exuberantly smiling women, one dressed in a fake-fur coat, with a leather belt and a white ‘bearskin’ hat. This originally military hat, made from black fur, was traditionally worn by the hussars, but today are mainly worn by majorettes and fanfare bands. The image is completed with a pair of Dr Martens-style military boots. The other model is wearing a military drab coat with shoulder epaulettes, brass buttons and a raised collar. A hat also betrays unmistakable military origins, though is described here as a party hat and comes from a party shop.

Including military elements in your wardrobe was seen in the period of ‘freedom and joy’ fashion as a light-hearted and carefree game. And that game was played mainly by fashion-conscious women, perhaps serving as forerunners to the more masculine power dressing, with extreme broad shoulders, which came to the fore in women’s fashion in the following decade.

Military references also reached the height of fashion in around 2000, with excessive displays of military and sports emblems such as stars, numbers and badges on both men’s and women’s chests and upper arms. These sewn-on features replaced the buttons which had previously underscored the wearer’s unique personality and which were used to make a specific statement.2

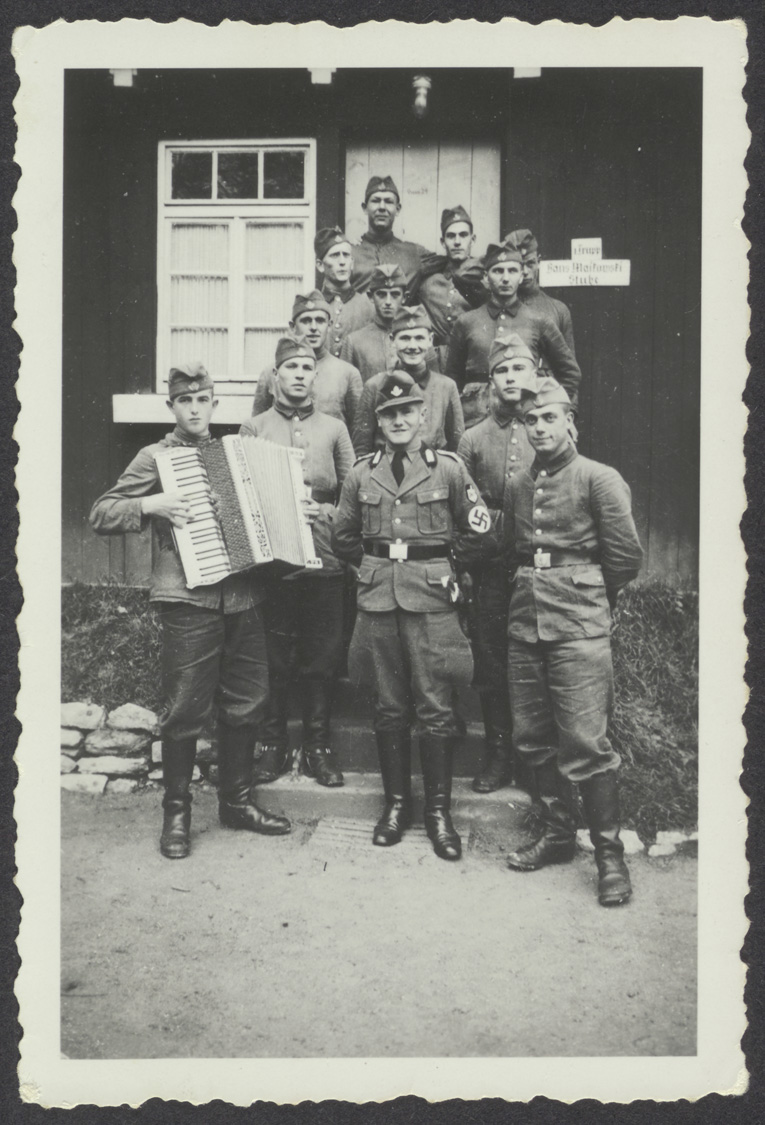

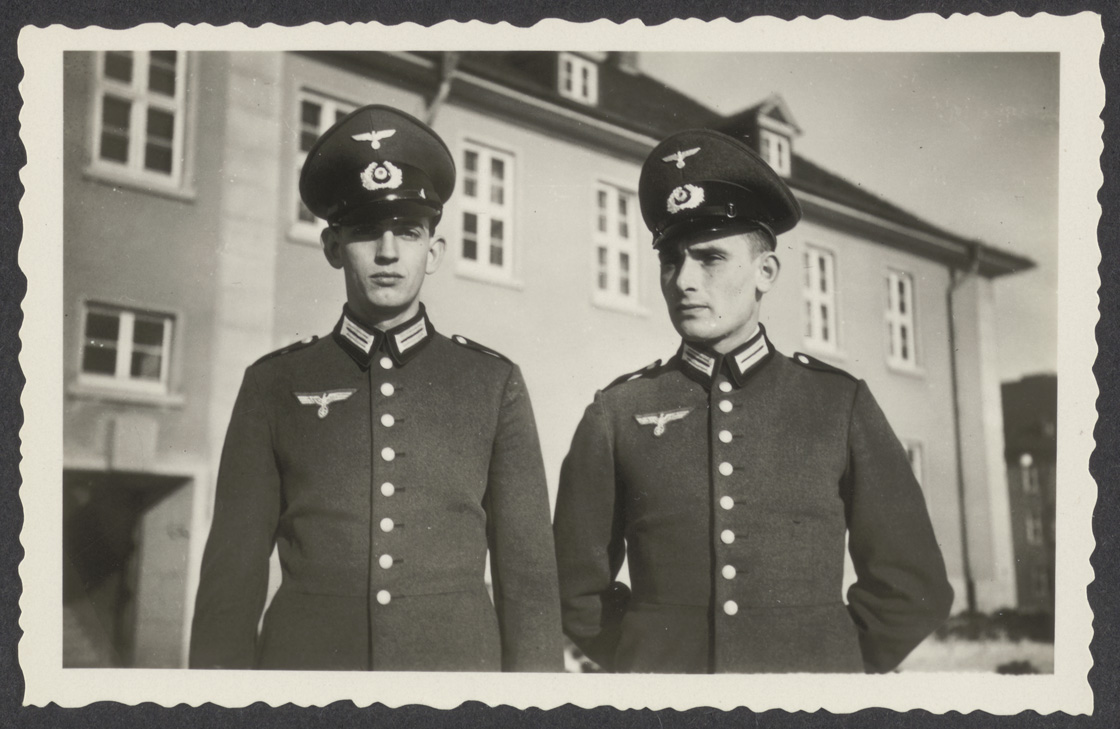

These links between fashion and the influence of military apparel are in fact rather odd. Because where in the fashion world they represent the expression of a particular standpoint, a desire to appear rebellious, to show the wearer’s individuality and turn the whole thing into a game, this is out of kilter with the image of the brave, long-suffering soldier, who – as the word itself says – dresses uniformly, with no trace of individuality, uniqueness, rebelliousness or game-playing. The serious, posed group photos from Gerrit Jan Vos’ collection provide a good insight into that uniformity from different periods and countries. There is no room for personality or any display of rebelliousness. Even the most informal snapshots lack any specific signs of individuality.

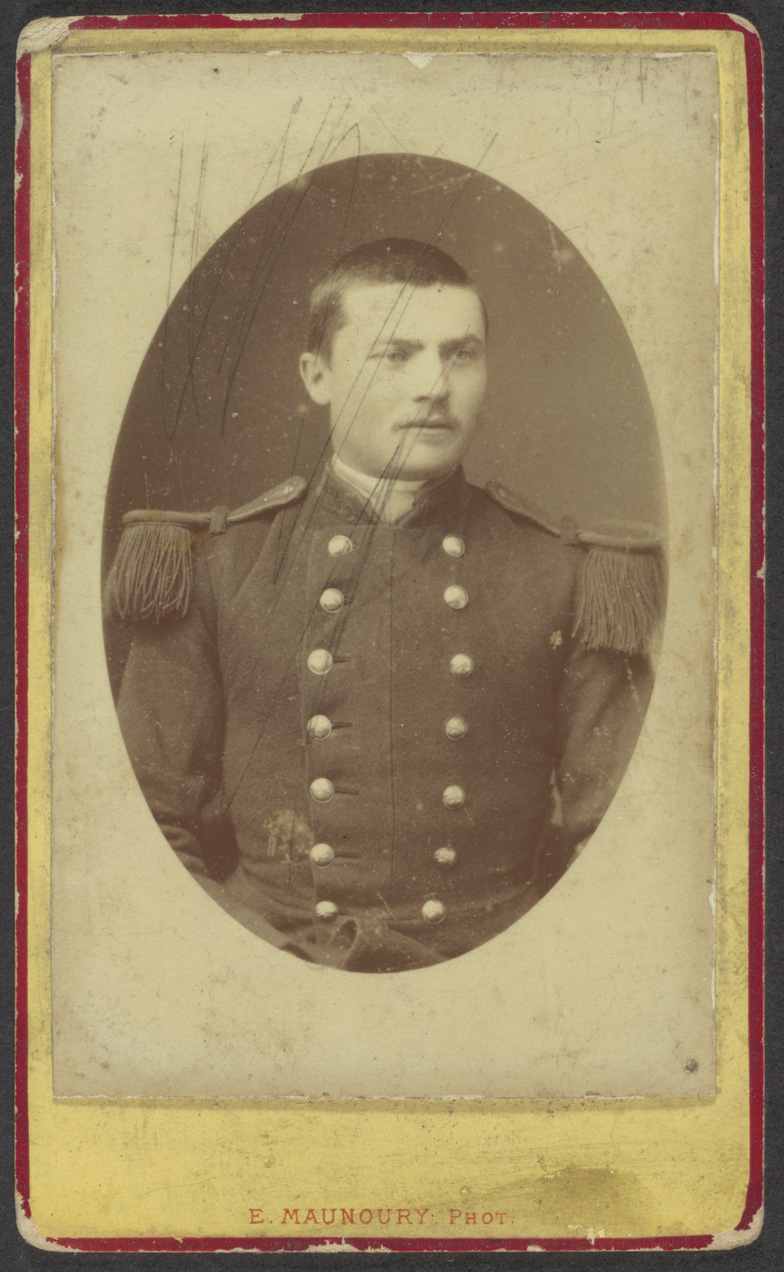

Uniform military dress must of course be functional, and among other things offer comfort and protection against the weather whilst camouflaging the soldier from the enemy. A uniform also makes it possible to identify and distinguish the wearer’s country, function and rank.

Power is also a key ingredient. Military dress is generally somewhat intimidating, because military uniforms make the wearer appear larger, broader and therefore stronger. The aim is to exude a visible sense of power.

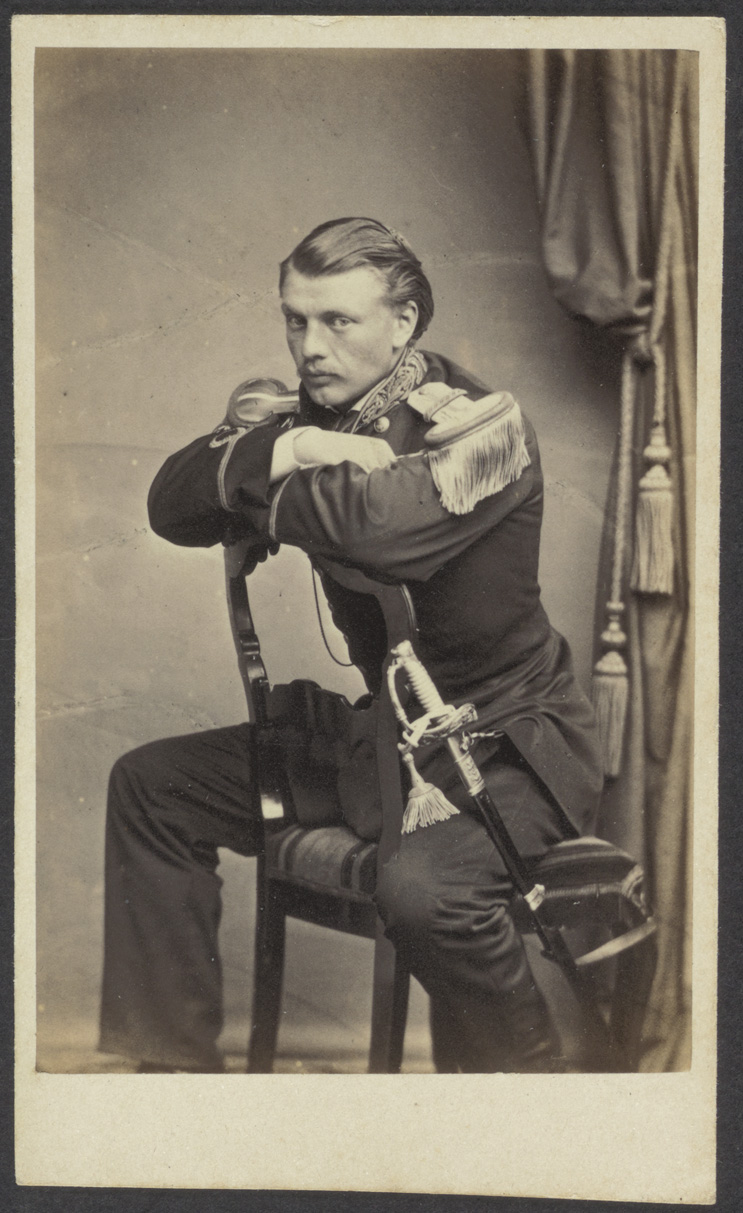

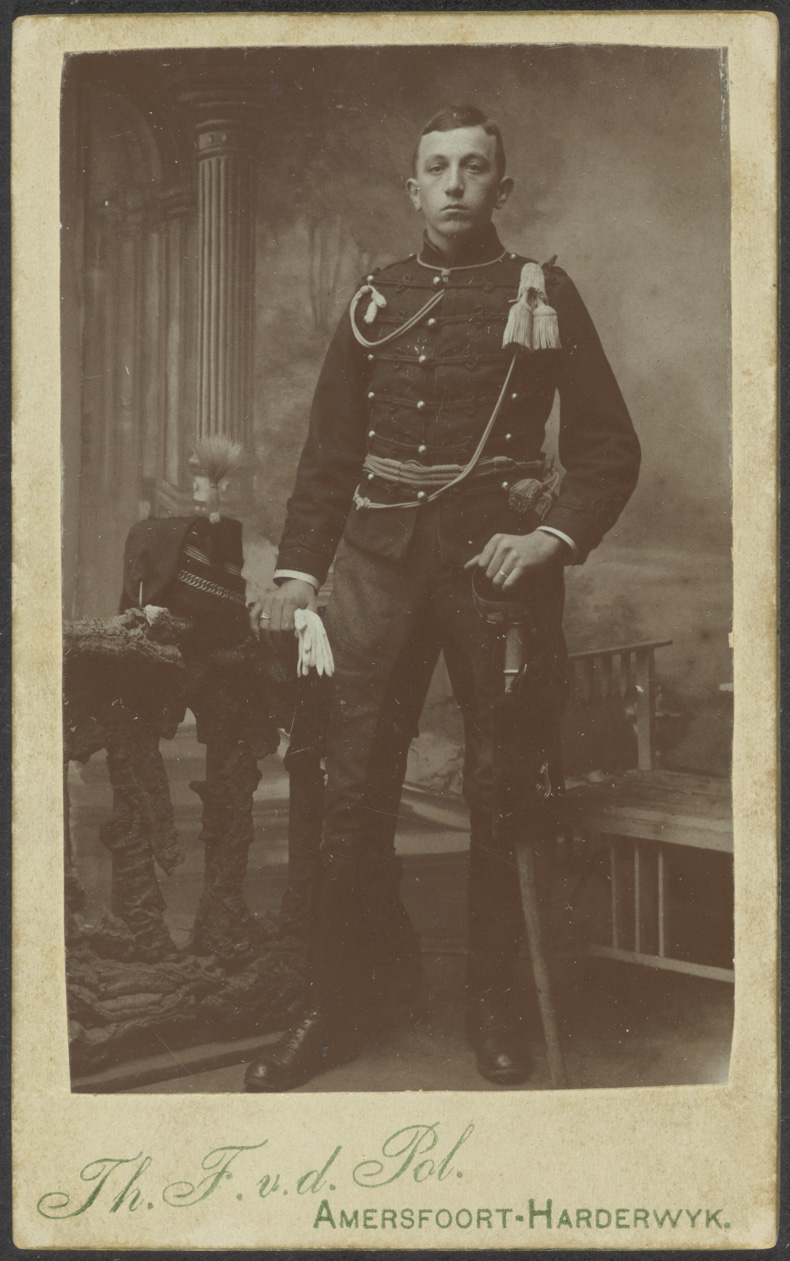

From a psychological perspective, this boosts self-confidence and the wearer’s subjective sense of safety. Filling the chest area with decoration and broadening the shoulders by adding epaulettes creates a more imposing impression. And fearsome spikes or decorative feathers on a helmet, a tall hat, shining buttons, lanyards, gold braiding and other decorative elements also help to transform an ordinary man into an imposing stallion, a superman.3

An additional effect is that power has an erotic quality, making the wearer seem attractive to others. In the 1955 film Pride and Prejudice, based on the book by Jane Austen (1813), accurately depicts the way in which the locally billeted and colourfully dressed soldiers set the pulses and imaginations of many an eligible young lady racing. And perhaps also many a male pulse, though the story does not touch on this.

Such forms of ostentation and adornment are often linked by sociologists, psychologists, fashion historians and other scholars to behaviours in the animal kingdom. Male animals are generally more richly adorned with feathers and colours, or have larger antlers or horns than females. Even James Bond is presented as an intimidating character.4

The scientific ideas point in all directions, but ultimately all come down to the same thing: it’s about making an impression. And there are many ways of doing this: the strutting peacock, like Louis XIV with his ostentatious wigs and red lacquered shoes; the dandy with that exaggerated attention for his appearance; right through to the secret agent 007 with his irreproachable conventional clothing symbolising competence, courage and stature.

Clothing can thus also be seen as a system of symbols, and that certainly applies for military uniforms. A broadened shoulder line, a row of medals, or feathers on the helmet are symbols designed to make an impression.

This dress-to-impress principle has been applied frequently in the history of fashion. Throughout the centuries, natural physical proportions have been replaced by an ever-changing ideal image. In the late Middle Ages, pointed shoes and headdresses, shaving off the hair on the forehead and moving the waistline suggested a longer body. From the 16th century onwards, this vertical silhouette was replaced by a horizontally orientated silhouette, with the emphasis being on greater breadth. Portraits of Henry VIII from this time show flat head coverings, widened shoulder lines with improbably large puff sleeves and flat shoes with square toecaps. The motto here was: the greater the volume occupied, the more important the person.

Similar principles can also be seen in the military dress in the Gerrit Jan Vos collection, for example through the addition of horizontal braiding to make the chest appear broader, lending even the most puny men a touch of superman power.

Uniformity and functionality at different levels (including dressing to impress) are standard elements in military uniforms, then. And dressing in a uniform changes the wearer from a unique individual (‘I’) to a member of a group (‘We’). However, it is human nature to want to distinguish ourselves from others. We think our personal clothing choice shows the outside world that we are a unique individual. By wearing those ‘unique’ jeans with the torn knees, that colourful baseball cap or those special trainers, we believe we are emphasising our personal identity.

At the same time, innumerable others are wearing the exact same clothing items, helping us feel safe within this generally imprecisely defined group. It is precisely this duality of uniqueness/group membership that the was recorded by the photographer Ari Versluis and stylist Ellie Uyttenbroek over several years in hundreds of photos, brought together under the title Exactitudes.5

They travelled the world putting together their collection. Each set brings together 12 individuals , each of whom assumed that they were unique. But photographed wearing their almost identical outfits, in the same pose against a blank background, makes them almost interchangeable. The way most people dress is more of a cliché than they think. The photos taken by this duo show virtually identical ‘frat boy’ types in their pale blue shirts and red trousers, Indo rockers with their leather jackets and sunglasses, and young management types with their dark suits, no tie and a large laptop bag slung across their shoulder.

Although the backgrounds and poses are different, many of the photos of uniformed soldiers in the Gerrit Jan Vos collection clearly create the same effect. These men, too, come from different countries, but that does not affect their universality. As with the Exactitudes images, their uniqueness and individuality are visible only in minuscule details. Even something as small and personal as holding a cigarette or placing a cap on a table appears to be a carefully considered symbol which matches the image they convey.

As well as the many ‘serious’ photos, the Vos collection also contains many informal, comradely photos showing sports and other activities. During these activities, the soldiers also wear government-supplied ‘uniforms’. Naturally, each man wears the clothing in their own way, but even during moments of relaxation and despite these minor differences, this is yet another example of uniformity.

A few photos of fancy-dress parties show more in the way of uniqueness. As no backgrounds are known to the photos, it is unfortunately not always clear whether the groups depicted are actually soldiers.

One photo shows a humorous group that is probably depicting the Nativity. Their identical military boots suggest that these are soldiers. The men appear to be wearing arbitrarily put together costumes. There is even someone in clerical garb, and could it be that the man on the left represents Joseph the carpenter?

It is a matter of guesswork what story the group with musical instruments are telling. The mix of soldiers and exotically clothed gentlemen with sabres or swords undoubtedly appealed to the collector’s imagination.

But non-military personnel can of course also dress up as soldiers. In the 19th century, it was standard practice among the well-to-do to throw fancy dress balls and themed dress parties in the winter months. Books were published giving tips on how to dress as various figures, including Neptune, an ancient Egyptian or a Bulgarian farmer or farmer’s wife.

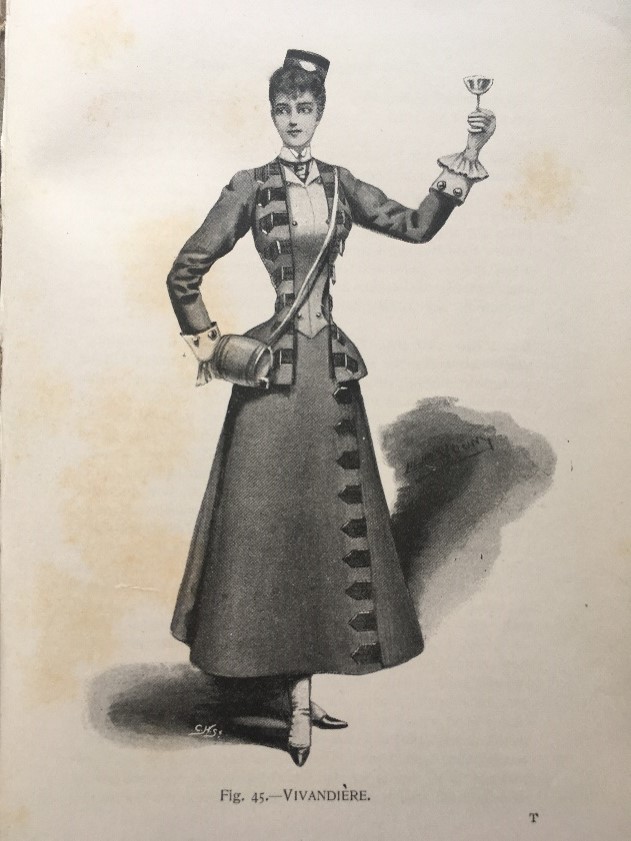

The vivandière (sutler or victualer) was also a popular subject. These women sold food and drink and other basic necessities to the troops in the barracks or on the front, and poured alcohol from a hip vessel. A book published in 1896 gives advice on dressing as the ‘daughter of the regiment’ from La fille du régiment, the popular comic opera by Donizetti, or as a victualer to the guard of King Louis XIII or Napoleon. Different fabrics and colours were recommended for the Polish, Hungarian, French or Russian armed forces. The sporadic drawings include one such victualer. Her fancy dress costume contains subtle references to military influences, but is dominated by the fashionable silhouette of that time.6

Beyond this, these books devoted scant attention to military accoutrements, and a German catalogue of party articles from 1911 offers only a paper infantry helmet, an army cap with feather and a decorated helmet.7

It is uncertain whether the photo of men dressed in apparently historical uniforms in the Gerrit Jan Vos collection is also a reference to such books. Their wigs and scarves were fashionable in the 18th century, and the mixture of Napoleonic symbols and bearskins gives them an imposing appearance. Might they have been dressed for a themed party, or acting in a play or tableau vivant?

The Vos collection also includes a number of photos in which it is not immediately clear whether they depict serious, impressive military uniforms or fancy dress costumes. Some of them may have formed part of a ‘masquerade’; these festive parades, which were very popular in the 19th and early 20th century, generally featured historical themes in which neither cost nor effort was spared. The masquerade committees regularly noted that the cuirasses they wore were not an entirely faithful reproduction of reality.

Fashion can be seen as a light-hearted game. Fashion-lovers have the freedom to use military uniform as a source of inspiration and to express their personal views to their heart’s content and to emphasise their individuality. Although in the first instance a military uniform serves practical functions and leaves no scope for individual expression, there are in reality a number of similarities to the system of symbols used in fashion.

There is one further element which has not yet been mentioned but which cannot be ignored: the desire to be pleasing to the eye; appearances matter. Aesthetics plays an important role in fashion clothing, and this also applies for military uniforms. They are generally made with great care from quality materials. The cut, colours, accessories, details and all manner of decorations are of great importance in emphasising the image.

Gerrit Jan Vos’ photo collection also shows that while military apparel has its own rules, at the same time it makes use of specific fashion effects. Conversely, fashion readily dips playfully into the military clothing dressing-up box.

- Viva, No. 34, 25 August 1978, cover and pp. 36-37. Viva no. 5, 2 February 1979, p. 21. Viva no. 38, 22 September 1978, cover and p. 25. Viva nr. 38, 22 september 1978, cover en pag. 25.

- See e.g. Marieta van Driel, ‘Nieuwe decoratietrend: emblemen’. In: Textilia, 4 October 2001.

- Ron Kaal, Superman komt naar de supermarkt, uniform in de mode. Volkskrant Magazine, 8 April 2000, pp. 54-57.

- Such theories began to emerge in the early 20th century. See e.g.: G. Simmel, Philosophie der Mode. Berlin, 1905; J.C. Flügel, The psychology of clothes. London, 1930; R. König, Sociologie van de mode. Utrecht, 1965; G.A. de Wit, Modekleding motivatie, een sociaalpsychologische studie van het mode-gebeuren. Haarlem, 1970; A. Lurie, The language of clothes, Feltham. 1981; L. Svendsen, Mode, een filosofisch essay. Kampen, 2007.

- Ari Versluis, Ellie Uyttenbroek, Exactitudes. Rotterdam, various editions between 2002-2014.

- Ardern Holt, Fancy dress described, what to wear at fancy balls. London, 1896, pp. 272-273

- Katalog über Cotillon-, Ball- and Scherzartikel, Saison 1911/12. J.C. Schmidt, Erfurt. Herdruk Hildesheim, 1999, p. 220.